![George Henry Moulton Compiled Military Service Record - Appears in Returns [partial]](36aColorGuard.jpg)

Corporal Moulton's last dated letter (February 9, 1864) concluded with a caution to his mother: "There is one thing I will say and close. Your love for showing my letters around don't work well for me, & if you show any more I must be careful what I write." The Moulton collection resumes with another letter to his mother, dated May 29, 1864. This is an unusually long laps in correspondence since Henry, on average, wrote home twice a month. This considered, it seems fitting to acquaint our readers with a couple of important events which occurred during this lapse in correspondence.

First, Henry's regiment was at Baton Rouge, in winter quarters, when he last wrote home but by April 1864 the regiment was preparing to join the Union's spring offensive which was already under way. 'The Red River Campaign', as the spring offensive was called, would be the largest combined army-navy operation of the war. Its objective was Shreveport, the capital of Louisiana and the Confederate headquarters of the Army of the Trans-Mississippi. Success here could open a gateway for the invasion of Texas, an offensive heavily sought after by President Lincoln. The land operation was commanded by Union Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, a native from Massachusetts and past speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. Banks saw the campaign as his gateway to become the Republican party's nominee for the 1864 presidential election. Henry and his regiment would be in the thick of things during this failed campaign, which turned out to be the South's last decisive victory of the war.

Second, Henry began his enlistment as a private and was promoted to corporal, March 1863 — an event he made little note of. A year later, March 1864, he was appointed to the regimental color guard, again barely mentioning the fact. The color guard was an honorable and prestigious unit and it can be said that those who served its cause knew well its perils.

Prior to the Civil War (1850s), a manual entitled Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics for the Exercise and Maneuvers of Troops When Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen was published. It was commonly referred to as "Hardee's Tactics" (author was Col William J Hardee) and was used by both Union and Confederate Armies. The manual spelled out the duties and responsibilities of infantry, including those of the color guard.

Today many of the Civil War re-enactment groups include a color guard. The Third Maine Regimental Re-enactors has on its website a good description of what the color guard was all about:

The honor of escorting a regiment's colors was given to individuals selected from the companies of the regiment as the color bearers and color guard. The color bearers were usually sergeants and the color guard were corporals. This select squad was placed in the ranks on the left of the color company, and the color company was placed just to the right of the regiment's center when it was in a line of battle. This arrangement placed the colors at the regiment's center. The color squad was composed of a national color bearer and a regimental color bearer with seven color guards... The color guard was a target of enemy fire and it took brave men to volunteer for this job. Capturing the colors was a battle trophy; losing your colors was a dishonor. The casualties in the guard were always high. When the bearer was unable to go on, another member of the guard would move forward to rescue the flag. The flag of the regiment served as a rallying point for the men and often indicated the location of its leaders. The flag and its bearer usually lead the regiment into battle, therefore offering themselves as the first target to the enemy.

Last month I contacted the Art Collections Manger at the Massachusetts State House to enquire about Civil War battle flags, in particular, the 38th Mass Vol. Inf. (Henry's regiment) and a few other regiments in which Milton soldiers served. The Collection Manager informed me that the flags were in storage and not available for public viewing or photographing but she offered and forwarded catalogue descriptions and color scans for the flags of the 2nd, 32nd, 35th, 38th, and 45th Massachusetts regiments.

This material has been incorporated into the George Henry Moulton collection at the Milton Historical Society. Brief summaries follow.

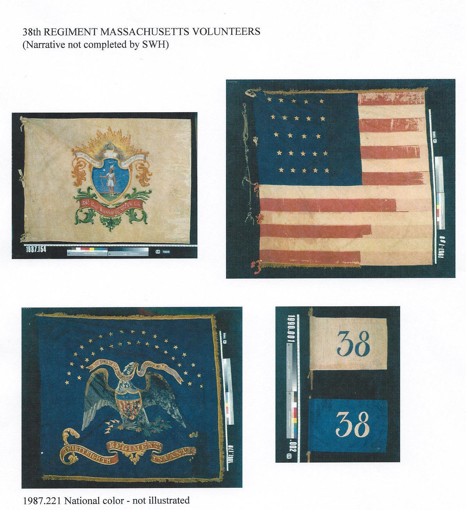

Thirty-Eighth Regiment:

George W. Powers' The Story of the Thirty Eighth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers is a helpful reference to read along with Henry's letters. For instance, Powers mentioned the Regiment received its first contingent of recruits on March 10, 1864 and then almost as an apology stated:

It should have been mentioned before, that the ladies of Cambridge, during the summer, had procured a very handsome silk flag, with the name of the regiment, and the engagements in which it had taken part, inscribed upon it in golden letters. This flag was forwarded to Baton Rouge, and entrusted to the care of the regiment...Five more battles were afterward placed upon its stripes.

This particular flag is not among the flags in the State House collection and may have been returned to the original donors. The State House flag collection does, however, include four flags of the 38th Regiment — their scanned images shown at right.

Second Regiment:

Alonzo H. Quint, author of The Record of the Second Massachusetts Infantry, states:

The United States Colors... was the battle-flag, used only in action, and carried in every engagement except Winchester. The tassels were shot off at Cedar Mountain, Its staff was shot in two at Antietam, and given to Mrs. William Dwight. The new staff was presented by Miss Fannie Mudge. That staff was shot into fragments at Gettysburg, and a new one was given by Miss Marie Louise Mudge and Feroline P. Fox. No hostile hand ever touched this flag, and it never knew dishonor. ...It now rests at the State House, with no names of battles on it.1

Quint's account of the Battle of Gettysburg and the conduct of the 2d Regiment's Colonel and color guard is particularly heroic and tragic.

At about 7 o'clock on the morning of July 3rd orders came to the Second, and one other regiment, to advance over the meadow, and carry the enemy's position. So strange an order excited astonishment. The regiments were a handful against the mass of enemy opposite, even without any regard to their formidable position. Lieutenant Colonel Mudge questioned the messenger, "Are you sure that is the order?" — "Yes." — "Well," said he, "it is murder: but it's the order. Up, men, over the works! Forward, double—quick!" With a cheer, with bayonets unfixed, without firing a shot, the line sprang forward as fast as the swampy ground would allow. The brave young leader fell dead in the middle of the field, as on foot and waving his sword, he was cheering on his men; and Major Morse took command. Three color bearers were shot in going two hundred yards, but the colors kept on. Into the enemy's line; up to the breast-works; and the regiment held its old position! But rebel fire was still terrible. The Second was alone. The regiment on its right, its single help, had melted back. The troop in support were motionless. From behind every tree and rock, the enemy poured an overwhelming fire; three brigades (a prisoner afterwards said) were at that point. Another color-bearer fell dead, waving the colors. Ten officers had fallen.2

Thirty-Fifth Regiment:

The 35th Massachusetts was posted initially to the Army of the Potomac, fighting at South Mountain, Antietam, and Fredericksburg under its blue and white colors. At Antietam the regiment fought at the famous "Burnside Bridge." After crossing the bridge the 35th pushed forward until it sat atop an open ridge, exposed to fire it could not effectively return. It was recalled, and in falling back was mistaken for an enemy advance and fired on by friendly artillery. The colonel called out to unfurl the colors and wave them, and the blue U.S. and white Massachusetts colors were recognized and the firing stopped. The 35th remained in position until dusk, fighting to the very last of its ammunition. Color-Sergeant Moses C. Bartlett, Company B, was wounded and taken off the field, Color Corporal Edmund Davis of Company I was badly wounded and later medically discharged. Finally Captain William S. King, in command of the regiment since the wounding of the colonel, and himself wounded seven times, was helped off the field, bearing off the colors to a place of safety, for by that time the whole color guard were disabled.3

Forty-Fifth Regiment:

The 45th Regiment was an outgrowth of the Independent Corps of Cadets, a company-sized organization in the Massachusetts Militia that had originally been raised as the governor's guard in 1741. The 45th was a nine months regiment and counted among its ranks 48 Milton soldiers, 38 serving in Company B, commanded by Captain Joseph Churchill.4

The Forty-Fifth was posted to the Department of North Carolina. There it took part in December 1862 in the three battles of Kingston, Whitehall, and Goldsboro. At Whitehall, on December 16, the regiment was placed in support of a battery busily engaged in a duel with Confederate artillery. As the regiment waited and watched, a rebel shell hit the ground just in front of the color guard, bounded up and hit Color-Sergeant Parkman in the side of the head, then passed on and landed near Colonel Codman. It failed to burst. Parkman was carried to the rear by members of the color guard, but never regained consciousness. Sergeant Parkman was son of a Boston minister, had graduated from Columbia College, studied chemistry in Germany, received a degree as Doctor of Philosophy, and studied a year at Harvard before enlisting in the 45th. It is surprising that he was content to serve as an enlisted soldier, when a commission would surely have been his for the asking. In 1904 a painting of Parkman was commissioned, and a copy was later made. One now hangs in Harvard's Memorial Hall, the only portrait of an enlisted man in the collection, near that of Parkman's cousin Robert Gould Shaw. [from: History of the Forty-fifth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteers by Albert W. Mann, 1908]

Thirty-Second Regiment:

The 32nd Regiment was the outgrowth of the First Battalion, Mass Infantry which was organized November 1861 to garrison fort Warren in Boston Harbor. This was a three year regiment and by the winter 1863/1864 the greater majority of the regiment had re-enlisted for another three years and as such the regiment was give a month's furlough. The regiment was hosted and honored with a cotillion at Faneuil Hall, where Governor Andrew addressed them:

I cannot, soldiers of the Union Army, by words, by eloquence of speech, in fitting measure repeat your praise. This battle flag, riddled with shot and torn with shell, is more eloquent than human voice, more speaking than language, more inspiring, more pathetic than music or song. This banner tells what you have done. It reveals what you have borne. And it shall be preserved so long as the last thread remains, so long as time shall leave a splinter of its staff — a memorial of your heroism, your patriotism and your valor.

The regiment completed its furlough February 17 and returned to the seat of war. On May 5, 1864, at the battle of the Wilderness, it suffered slight loss. The Regiment moved to Spotsylvania May 8, and was heavily engaged on the 12th near Laurel Hill, losing 103 men including five color bearers, 46 being killed or mortally wounded.5

By the Spring of 1865, Grant's forces had Lee's army fairly well contained. On the evening of April 1, Col. James Cunningham of the 32nd Regiment was placed in command of a brigade of skirmishers, consisting of one regiment from each brigade in the 1st Division, with orders to deploy them at eight o'clock the next morning — the 32nd was of course, one of these regiments and its command devolved upon Captain Bancroft.

Sunday morning, promptly at eight o'clock, the order "Forward" was given and the right and left general guides fairly sprang to their positions. The enemy being in full sight no skirmishers preceding us. The advance was made under a sharp artillery fire, the men stepping out with a full thirty-six inch stride. The enemy's front line was slowly falling back. Then Colonel Cunningham, through his field-glass, seeing what seemed to be a flag of truce in our front, took the adjutant with him, and putting spurs to their horses, they dashed forward, and soon met a mounted officer attended by an orderly, bearing a small white flag upon a staff. This officer announced himself as one of General Lee's staff, and said that he was the bearer of a message to General Grant with a view to surrender.

After Grant and Lee met and the terms of surrender were agreed upon, April 11 was set as the day for the formal surrender of arms. At nine in the morning the brigade was formed in line on a road leading from our camp to that of the Confederates, its right in the direction the latter. The 32 d Massachusetts was the extreme right of the brigade. The Confederate troops came up by brigades at route step, arms-at-will. In some regiments the colors were rolled tightly to the staff, but in others the bearers flourished them defiantly as they marched. As they approached our line, our men stood at shouldered arms, the lines were carefully dressed, and eyes front. Seeing which, and appreciating the compliment implied, some of the enemy's brigadiers closed up their ranks, and so moved along our front with their arms at the shoulder. Their files marched past until their right reached to our left, when they halted, fronted facing us, stacked their arms, hung their accoutrements upon the rifles, and then the color bearers of each regiment laid his colors across the stacks, and the brigade, breaking to its rear, gave room for the next to come up in its place.6

As mentioned above, the next letter in the Moulton Collection will be released May 28th. Henry, now recovered from the wound he received during the assault on Port Hudson, is set to rejoin the regiment, which is about to embark on the Red River Campaign. He is no longer a boy but a seasoned veteran and shares his feelings on: Massachusetts' treatment of its soldiers — particular those at the U.S. General Hospital at Readville, Mass; how some of Milton's citizens only pay lip-service to the war effort; the failure of the draft; the government's delinquency in meeting soldiers' payroll commitments; the ninety day enlistees; the prisoner parole/exchange program; politicians, generals and the 1864 presidential race; and the assassination of President Lincoln.

Tell your friends and associates about the 'George Henry Moulton Civil War Letter Collection' — it only takes a Society membership and they will have access to all previous issues and to two dozen more letters through May 7, 2015.

Editor: Dennis (Mike) Doyle

1 Miss Fannie Mudge and Miss Marie Louise Mudge were Lt. Col. Mudge's sisters.

2 Col. Mudge's second cousin was Joshua W. Mudge, the "brother Mudge" that Henry mentioned in two of his letters — both Mudges were from Lynn. Joshua Mudge will be footnoted again in an upcoming letter.

3 Excerpt from Steve W. Hill, State House Flag Historian. See also Corporal Charles W. Cook's journal — Milton Historical Society website.

4 Captain Joseph McKean Churchill was born in Milton 1821, son of Asaph & Mary (Gardner) Churchill. George E. Tucker was a Milton/Dorchester resident. He was a member of the regimental color guard and a sergeant In Churchill's company. He was the son of Elisa Tucker of Canton and Mary A Houghton of Milton.

5 Patrick Dunican, from Milton, a member of Company G, 32nd Regiment was one of the soldiers killed at Laurel Hill.

6 This account of the Thirty-Second Regiment is derived from The Story of the Thirty-Second Regiment Massachusetts Infantry by Francis J. Parker, Colonel, published Boston, 1880. The Regimental History, unfortunately, does not contain the muster roll of its soldiers or the names of its color bearers/guards. Colonel James Adam Cunningham joined the regiment as first lieutenant and advanced through promotion to be brevetted a Brigadier General. He was born in Boston but moved to Gloucester. After the war he was Adjutant-General of Massachusetts Militia. Luther Ford was from Milton. He joined the regiment in 1863 and had the unique and patriotic experience to be present at the surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox Court House. He married Ann Maria Hunt of Milton. They had ten sons, the second he named after himself, the rest after notable people (George Washington, Edward Everett, Daniel Webster, William Grant, Charles Sumner, James Wilson, Arthur Garfield, Benjamin Harris and Henry Beecher). His son Edward Everett owned and operated a dairy business from Hillside Street until his death in the early 1950s. The 'Cook-Ford Barn', built in the late 1870s, still stands at 189 Hillside Street, Milton.