|

|

A Hero for Heroes, Nailed beneath the basement staircase in this writer’s home is a welcome sign, artfully traced out on white cardboard, with polychrome embellishment, reflecting the thoughtfulness of its creator. It was put there in 1942 by the departing occupant for my incoming family. Though then not yet a member of the family, I have been no less proud or gratified than they that the sign has been reverentially preserved, in the same exact spot, for 65 years now. The reason is that its maker, our home's first owner, was Edward Allen Gisburne — Congressional Medal of Honor recipient.

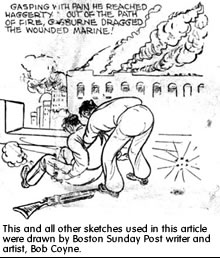

But what distinguished Eddie Gisburne as even more extraordinary amongst America's most extraordinary heroes, were commendable contributions he made for his country after already having received his Medal of Honor for bravery. In a piece penned for the May 17, 1942 Boston Sunday Post,* writer and artist Bob Coyne described the “breathless hush” that had hung over our country in 1917, before America’s entry into World War I then raging in Europe. At recruiting stations, Coyne said, there were “long lines of young men eager to go over there, to fight in a great cause. Among those waiting at one Boston station was a young man: he was tall and well-built, but he had only one leg.” The one-legged lad was 21-year-old Edward A. Gisburne. And some of the enlistees waiting in the queue could only smile at his magnanimous spirit, thinking that no one with so serious a physical impairment, after all, could really expect he may be considered for military assignment. But when Gisburne presented himself to the recruiting officer, Coyne continued, “those who had been amused were amazed at what followed. The officer, noting a medal in Gisburne's lapel, rose to his feet. “‘It is a rare occurrence to meet one who has merited the Congressional Medal of Honor,’ he said. ‘You are probably one of the youngest to have ever received it. And I consider it a privilege to greet you.’ In this way Gisburne re-entered the U.S. Navy.” One may better appreciate the immense esteem that lay behind the recruiter’s greeting, by knowing that President Harry Truman once told a Congressional Medal of Honor recipient: “I would rather have this medal than be President of the United States.” And, in light of his own profound respect, General George S. Patton might be forgiven for his characteristically excessive exuberance in having once said: “I would give my immortal soul to receive the Medal of Honor.” Of course, not even a Congressional Medal of Honor would be enough to earn admission into active duty with a missing leg. Eddie Gisburne first had to get a waiver directly from Secretary of War Daniels himself. Preamble to Valor

Once a Hero . . . In the course of the battle, according to Bob Coyne’s account, and under intense fire, Gisburne made his way to the roof of the Terminal Hotel, presumably to set up radio contact. With him on the rooftop was a marine from Cambridge whose name was Haggerty. “So heavy was the beating of bullets that Gisburne was knocked down,” wrote Coyne. “As he rose to his feet, he saw Haggerty slump and fall so that part of his body dropped beyond the edge of the roof. . . . Without thought of [the] heavy fire he rushed toward the wounded marine. But Rebels had the place spotted. Bullets seemed to be all about him and he pitched forward. The roar in his ears was so terrific that it seemed as though worlds were tumbling about him and pains stabbed his body. “It was an ugly sight and of course especially painful, but Gisburne ignored his own great need. Close by was one whose need was greater. Somehow Gisburne dragged himself the short distance; but even that effort almost cost his life. It took his last ounce of strength and his hands, from which the flesh had been torn, showed how much those few feet cost. “Gasping with pain, he reached Haggerty. The marine was torn with bullets, yet when Gisburne dragged his broken body from its perilous position, there was a quiver of recognition in those almost sightless eyes as though he [Haggerty] were grateful. Out of the path of fire, Gisburne dragged the wounded man into a shelter on the roof. “For a few moments Haggerty rested quietly in Gisburne's arms and then as though he were weary he drifted into the mystery and the silence. But even before he had passed, Gisburne slipped into unconsciousness. There they found them: the dead body of a marine at rest in the arms of a blue-jacket who was close to the end himself. Only his indomitable will to live saved him, brought him through, after months of suffering, to face life with only one leg.” The only remarks young Eddie made after his rescue were: "Haggerty was brave. I saw him shooting it out. He never drew back." He was mute regarding his own selfless heroics. But the Congressional Medal of Honor awarded him by the President of the United States, on June 15th the same year, compensated for young Gisburne’s personal reticence.

One of his fondest memories from that second wartime stint was serving on the transport ship, the George Washington, when it carried President Wilson to Europe. After the war, he returned to civilian life in Milton where, during his 35 years of residence, he and his wife Ena raised their two boys. In succeeding years, he would: teach radio courses at Boston College; serve as a reporter for the Quincy Patriot Ledger; become district manager of Boston Edison; and serve as continuity editor for Radio Station WEEI. He would also hold memberships in the Engineers Club of Boston and the Wollaston Golf Club (where Coyne said he was a “firstrate performer and . . . won many trophies”). As busy as all those activities must have kept him, however, Ed Gisburne was fervently committed to civic responsibilities. A member of the Milton Town Club and active in town affairs, he was twice elected to the Milton School Committee Ever a Hero

But that was still just five months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Not much later – perhaps shortly after selling his Otis Street home to my parents and moving to upper Waldeck Road – Eddie, Sr. did, in fact, manage to “re-up” once again, despite being not merely an amputee, but now a 50-year-old one! This time, he returned to service as a commissioned Navy lieutenant, and was stationed at Quonset, Rhode Island.

It was July 21, 1945, when the Milton Record sadly announced: “Word has been received by Lt. and Mrs. Edward A. Gisburne of 80 Waldeck Road, that their son, S. Sgt. Edward A Gisburne Jr., was reported missing in action May 26, while on an air mission. . . . He had been awarded the Air Medal for outstanding performance in serial combat against the Japanese.” The tragic outcome of that nightmare was that the Gisburne’s eldest son, at age 29, had in fact been killed in action in his B-29. In 1950, the couple relocated to Duxbury. And on August 29, 1955, Eddie, Sr. himself, passed away, at age 63, at the Chelsea Naval Hospital. God alone can properly reward the sacrifices of life and limb and model commitment rendered by the Gisburne Family – and especially by Eddie, who lost not only his leg but his decorated son in service to his country – and who not only performed with exemplary valor in one war, but served admirably in two world conflagrations after that.

Towards the rear of Milton Cemetery, just off Circle Avenue, with two strong oaks symbolically standing close by, can be found the Gisburne family plot. It contains graves for Eddie, his wife Ena, and their son Edward, Jr. — though the remains of the latter actually were never recovered. It is heartwarming to see the son’s name included on memorials, in both the Town Hall and the Central Library, that commemorate our town’s war dead. A bronze plaque has been added to the father’s grave as well. But certainly more than merely a small plaque is due — from Milton and from all of American society — to honor a man of such remarkable bravery, sacrifice, and service to his country far above and beyond the call of duty. Is it unreasonable to think that monuments ought to be erected for him? That streets, parks, schools, bridges, public buildings should be named after him? This only seems fitting, since those same kinds of tribute so frequently are lavished on politicians simply for having warmed a seat in some political office. Now that Milton again is home to a state governor, perhaps at least one such long-overdue, much-deserved honor will finally be accorded this Milton hero, Navy Lt. Edward Allen Gisburne, Congressional Medal of Honor recipient. In the meantime, a small, very old, cardboard welcome sign still remains nailed to my home’s basement staircase as my family’s own, special little monument that for us says: “A Very Great Man Once Lived Here."

|

There is no higher honor than the Congressional Medal of Honor, awarded for distinguished valor in action against an enemy force. Only two CMOH recipients are buried in Milton Cemetery: The other, besides Edward “Eddie” Gisburne, is a German-born Milton resident named Paul Weinert, who so distinguished himself in battle at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, as to merit this coveted medal. To deny nothing of Weinert’s unquestionable bravery in 1890, however, it should also be realized that the standards of heroism in awarding the medal had been set even higher by Gisburne's time.

There is no higher honor than the Congressional Medal of Honor, awarded for distinguished valor in action against an enemy force. Only two CMOH recipients are buried in Milton Cemetery: The other, besides Edward “Eddie” Gisburne, is a German-born Milton resident named Paul Weinert, who so distinguished himself in battle at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, as to merit this coveted medal. To deny nothing of Weinert’s unquestionable bravery in 1890, however, it should also be realized that the standards of heroism in awarding the medal had been set even higher by Gisburne's time.

Eddie had been born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1892, but received his early education in the Quincy schools, and in Washington, D.C. At age 18, months before the Great War in Europe had broken out, his first enlistment in the Navy brought him into the little-remembered tempest at Vera Cruz during one of the many revolutionary upheavals that gripped Mexico spanning across two centuries. Francisco Madero, who had been elected President of Mexico by the largest margin of the popular vote to that time, was overthrown and murdered by a thug named Gen. Victoriano Huerta, described as "a drunkard and repressive dictator . . . almost too bad to be true."

Eddie had been born in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1892, but received his early education in the Quincy schools, and in Washington, D.C. At age 18, months before the Great War in Europe had broken out, his first enlistment in the Navy brought him into the little-remembered tempest at Vera Cruz during one of the many revolutionary upheavals that gripped Mexico spanning across two centuries. Francisco Madero, who had been elected President of Mexico by the largest margin of the popular vote to that time, was overthrown and murdered by a thug named Gen. Victoriano Huerta, described as "a drunkard and repressive dictator . . . almost too bad to be true."  In April 1914, a supply boat from the U.S.S. Dolphin, in Mexican waters on a diplomatic mission, was seized by Huerta's henchmen, and its crew arrested and paraded through the streets as a gesture of deliberate insult and provocation against the United States government. Even after Huerta's regime flatly refused to apologize for the incident, President Woodrow Wilson responded with bewildering restraint, telling Congress: "There can in what we do be no thought of aggression"! Congress emphatically disagreed, and authorized sending marines into Vera Cruz. Carrying the forces that would subdue the city after three days of fierce battle, which began on April 21, were three Navy vessels: the Prairie, the Utah, and the Florida. Electrician Third Class Eddie Gisburne was aboard the latter ship.

In April 1914, a supply boat from the U.S.S. Dolphin, in Mexican waters on a diplomatic mission, was seized by Huerta's henchmen, and its crew arrested and paraded through the streets as a gesture of deliberate insult and provocation against the United States government. Even after Huerta's regime flatly refused to apologize for the incident, President Woodrow Wilson responded with bewildering restraint, telling Congress: "There can in what we do be no thought of aggression"! Congress emphatically disagreed, and authorized sending marines into Vera Cruz. Carrying the forces that would subdue the city after three days of fierce battle, which began on April 21, were three Navy vessels: the Prairie, the Utah, and the Florida. Electrician Third Class Eddie Gisburne was aboard the latter ship.  Such uncommon bravery, especially at the cost of a limb, would be far more than enough service for one man to his country. As his commanding officer said of him: "He is entitled to every consideration from his countrymen and his country." But, as already indicated by Bob Coyne, it wasn’t enough for Eddie. Since the Civil War, six generations of his family had served in the Navy, so he wasn’t going to let a threeday battle in Mexico and the absence of a leg define his total service. "I couldn't break with tradition," said Gisburne, "I knew there was a place for me." And there was indeed. An expert in radio, he handled all communications of Atlantic cruisers and transports throughout World War I. "Whatever I do, let me do it my way. I am not a cripple," was the personal code he drafted and adopted for life.

Such uncommon bravery, especially at the cost of a limb, would be far more than enough service for one man to his country. As his commanding officer said of him: "He is entitled to every consideration from his countrymen and his country." But, as already indicated by Bob Coyne, it wasn’t enough for Eddie. Since the Civil War, six generations of his family had served in the Navy, so he wasn’t going to let a threeday battle in Mexico and the absence of a leg define his total service. "I couldn't break with tradition," said Gisburne, "I knew there was a place for me." And there was indeed. An expert in radio, he handled all communications of Atlantic cruisers and transports throughout World War I. "Whatever I do, let me do it my way. I am not a cripple," was the personal code he drafted and adopted for life.  In May of 1942, Bob Coyne could only bring his article to a close by tentatively observing: “The Gisburnes carry on. A son, Edward, Jr., is an aviation cadet. Friends believe that only armed force will keep Edward, Sr., from once again taking his place in the list of recruits.”

In May of 1942, Bob Coyne could only bring his article to a close by tentatively observing: “The Gisburnes carry on. A son, Edward, Jr., is an aviation cadet. Friends believe that only armed force will keep Edward, Sr., from once again taking his place in the list of recruits.”  His son John also had entered active service. And the junior Edward Gisburne was serving in the Pacific theater, attached to the 40th Bomb Group.

His son John also had entered active service. And the junior Edward Gisburne was serving in the Pacific theater, attached to the 40th Bomb Group.