|

|

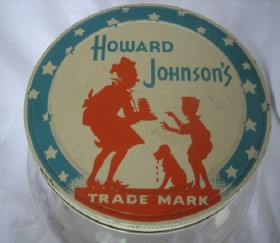

The Story of Howard Johnson's by Howard Dearing Johnson — 1938 If this brief biography seems to bear heavily on the capital letter "I," my defense is that the history of the Howard Johnson's Restaurants is my own history. Their beginning was mine; their reputation was mine to preserve. From Maine to Southern Connecticut, and now [1938] expanding into New York State, (our first in New York located on the Jericho Pike, Garden City, Long Island) today the name of Howard Johnson means to a growing multitude "the man who operates our favorite roadside eating-place." That was true when I opened my first restaurant; it holds good today though they number nearly a hundred; and however many there may be in the future, I mean to keep that reputation. An old-fashioned, hand-cranked ice cream freezer laid the foundation of the Howard Johnson's Ice Cream Shops and Restaurants. Ten years ago I was operating a small news stand in Wollaston, Massachusetts. To add to my "income" I began selling home-made ice cream made in the store's backroom. I was repaid for my efforts by the enthusiasm with which people bought my ice cream — bought it so fast that I and the hand-operated freezer could not keep up. That was bad, because everyone knew that you couldn't make ice cream in large quantities and still keep that distinctive "home-made" flavor and texture. "Everyone knew!" There's an old Yankee saying: "It ain't the things a man don't know that makes him a fool, it's the awful lot of things he do know that ain't so." I found out the truth of that by studying ice-cream making, experimenting with mixtures, invention new ones, until at last I hit on a formula which could be turned out in quantity and which suited my taste. More important, it seemed to suit many other people, for more and more began to come driving in to Wollaston to ask for "some of that Howard Johnson's home-made ice cream." Naturally I wanted to expand the business, and I saw a new way to reach many thousands of customers. Day after day more automobiles hurried along the highways, and more highways were built to accommodate them. America was on wheels, driving farther, s topping more often to eat away from home, away from the cities and their downtown restaurants. Where did they stop to eat? Well, you remember the first roadside stands which were thrown together to push carelessly-cooked food at the hungry motorist. "He'll never come back this way — give him anything." Again I didn't believe that. I figured that America really preferred good food, nicely served; I built the first Howard Johnson's stand on that belief, making it as attractive as I knew how, easy to look at and hard to forget. I put in my Home-Made Ice Cream, and because frankfurters were growing in popularity, I served a special Howard Johnson's Frankfurter, grilled in pure creamery butter. And again I was right. People did like the better food, and they did come back, again and again. Because of this increasing patronage, the next year I was able to build two more shops and serve other dishes. But I moved slowly; no food was added to the menus until I was satisfied that people wanted it and that I could prepare and serve it to suit them. Once found, the accepted recipe and method became a strict formula, followed to the letter in every one of my shops, as are my standards of quality, attractiveness and cleanliness. This uniformity has, I believe been one of the strongest aids in the rapid growth of the business throughout New England, so that still the name of Howard Johnson means "the man who operates our favorite roadside eating-place." This enterprise is more than an individual's success, it is a family affair and the original owners — my mother, my three sisters and myself — still [in 1938] control it. To the young men and women who started out with us, worked so hard and grew with the business we give a full share of the credit for success. NOTE: Even Johnson's two young children worked in the family business — son Howard and daughter Dorothy were featured proclaiming "We love our daddy's ice cream" on highway billboards.

Although his orange roofed empire began in Quincy, Howard Johnson lived in Milton from 1939 until his death in 1972. The 'host of the highways' had two homes in Milton — the Hallowell mansion on Brush Hill Road; and later the French Chateau style home on Metropolitan Avenue. When Mr. and Mrs. N. Penrose Hallowell, Jr. were passing papers in their 20 room Brush Hill Road home with Howard Johnson, Mrs. Hallowell expressed the hope that Mr. and Mrs. Johnson would be as happy in the house as Mr. and Mrs. Hallowell had been. After a prolonged silence 9 year old Howard [who had accompanied his father], piped up, "There isn't any Mrs. Johnson. One's dead and one's divorced. But Daddy's got a girl friend." Mr. Hallowell then rose from his fireside chair, smote Mr. Johnson, Sr. smartly on the back, and speaking for the first time said, "Bully for you, Johnson." — Who Killed Society? Cleveland Amory Howard Johnson once remarked "I never played golf. I never played tennis. I never did anything after I left school. I ate, slept, and thought of nothing but the business."

|